Fenway Court: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

- Diana Dinverno

- Mar 31, 2017

- 5 min read

Boston and Fenway. For baseball fans, the words conjure the home of the Boston Red Sox since 1912. For art and history lovers, they are directions to Fenway Court, the residence and art education center built by Isabella Stewart Gardner. My baseball loving husband and I recently visited the museum and agree that Fenway Court may be the brightest jewel in the city’s cache of riches.

Isabella Stewart, born in New York City in 1840, was the sole surviving child of David Stewart who made a fortune in Irish linen and mining. She married Jack Gardner in 1860 and moved to Boston. The couple traveled to Norway, Russia, Japan, Cambodia, China, India, Egypt, Nubia (today, northern Sudan and southern Egypt), Palestine, Athens, across Europe, and spent significant periods in France, Italy, and London. Interested in historical architecture, art, and exotic cultures, Gardner began selecting objects of art for their Boston home. With a discerning eye, she acquired works by Botticelli, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Manet, Degas, Whistler, Matisse, and many others. She was a friend of author Henry James, and numerous artists, including American painter John Singer Sargent.

Gardner’s passion for collecting quickly outgrew her Beacon Street home. She purchased a parcel of land outside the Boston city center in Fenway. In this popular, new area designed by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, she oversaw construction of Fenway Court, a grand Venetian style palazzo to house her art. She created a charter “for the purpose of art education, especially by the public exhibition of works of art.” In 1901, she moved into Fenway Court’s fourth floor, and thereafter, opened her home for concerts and public art exhibitions.

Fenway’s design turns the facades of a Venetian palazzo inward to form a courtyard filled with vegetation, fountains, Roman statues, and a second-century mosaic floor. Balconies overlook the courtyard and an immense skylight provides natural light.

Each themed room and gallery overlooking the courtyard is a treasure trove. With few exceptions, the art is unmarked so information sheets in each room provide detailed descriptions of the room’s contents. We started our tour in the Gothic room on the third floor, and viewed John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Gardner, painted long before Fenway’s construction. Her image accompanied us as we wandered the space she created for the public’s enjoyment.

In later years, Sargent stayed with Gardner when he traveled to Boston and used the Gothic Room as a studio.

The Gothic Room has many religious artifacts, including this Madonna and Child by Italian Renaissance artist Lorenzo Ghiberti.

View from inside the Gothic Room into the hallway leading to the short gallery.

Third floor gallery.

At the end of the hallway, I found Sandro Botticelli’s The Madonna of the Eucharist.

I also discovered this Giovanni della Robbia relief dating from about 1515-1520.

Ceiling of the Veronese Room.

In the flame-red Titian room, the artist's painting of Europa (1561-1562) depicts a scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The cream colored fabric below the painting was a panel from a dress that belonged to Gardner. She thought it so beautiful she repurposed it as a wall covering.

Another image of the Titian Room.

On the second floor, in the Early Italian Room, I was stunned to find a portrait by Masaccio, widely recognized as the first Italian Renaissance painter. Unmarked and tucked into a corner, it was a thrilling surprise.

Isabella Stewart Gardner was the first American to acquire work by Raphael. In the Room named for the artist, she presents the portrait of Count Tommaso Inghirami, who was born in 1470 and died in Rome in 1561. He served the Borgia and Medici popes. Julius II appointed him chief librarian of the Vatican. The Raphael room also displays a late-period Botticelli, Tragedy of Lucretia.

In the second floor’s Short Gallery, we saw a portrait of Gardner in Venice by Anders Zorn. In the painting she has just entered a room where an after-dinner concert has concluded. She has been on a balcony overlooking the Grand Canal watching a fireworks display. In his diary, her husband describes the evening and reports she said: “Come out—all of you. This is too beautiful to miss.”

In the same room, we found Gardner’s extensive drawing collection that includes work by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Matisse.

The star of the Dutch Room is an exquisite self-portrait by Rembrandt van Rijn (1629).

A number of empty frames overshadow other important paintings in this gallery. In 1990, thieves dressed as Boston police officers entered the museum and stole thirteen works of art, the most valuable from this room.

Two Rembrandt paintings, including The Storm of the Sea of Galilee (1633), and Jan Vermeer’s The Concert (1658-1660), disappeared that night and have yet to be recovered. The Vermeer was at a small table by the window. Although the artwork is gone, visitors still pause to look. Gardner’s will forbids changes to the art installations, so the frames remain as reminders of the loss and the hope for the works’ return.

On the ground floor in the Spanish Cloister, we found John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo (1882). Hubby was impressed.

Entrance to the courtyard from the Spanish Cloister.

A selfie in the light-filled Chinese Loggia, adjacent to the Spanish Cloister. It contains a Buddhist votive piece dating to A.D. 543 and other early Chinese works.

In the tiny Yellow Room on the ground level, paintings crowd the walls, including works by Whistler, Degas, and Matisse. This is James McNeill Whistler's Nocturne, Blue and Silver: Battersea Reach (purchased 1895). The photograph does not do it justice. In person, it is mesmerizing.

On the top right, is The Terrace, St. Tropez (1904). This is the first painting by Henri Matisse to enter an American museum.

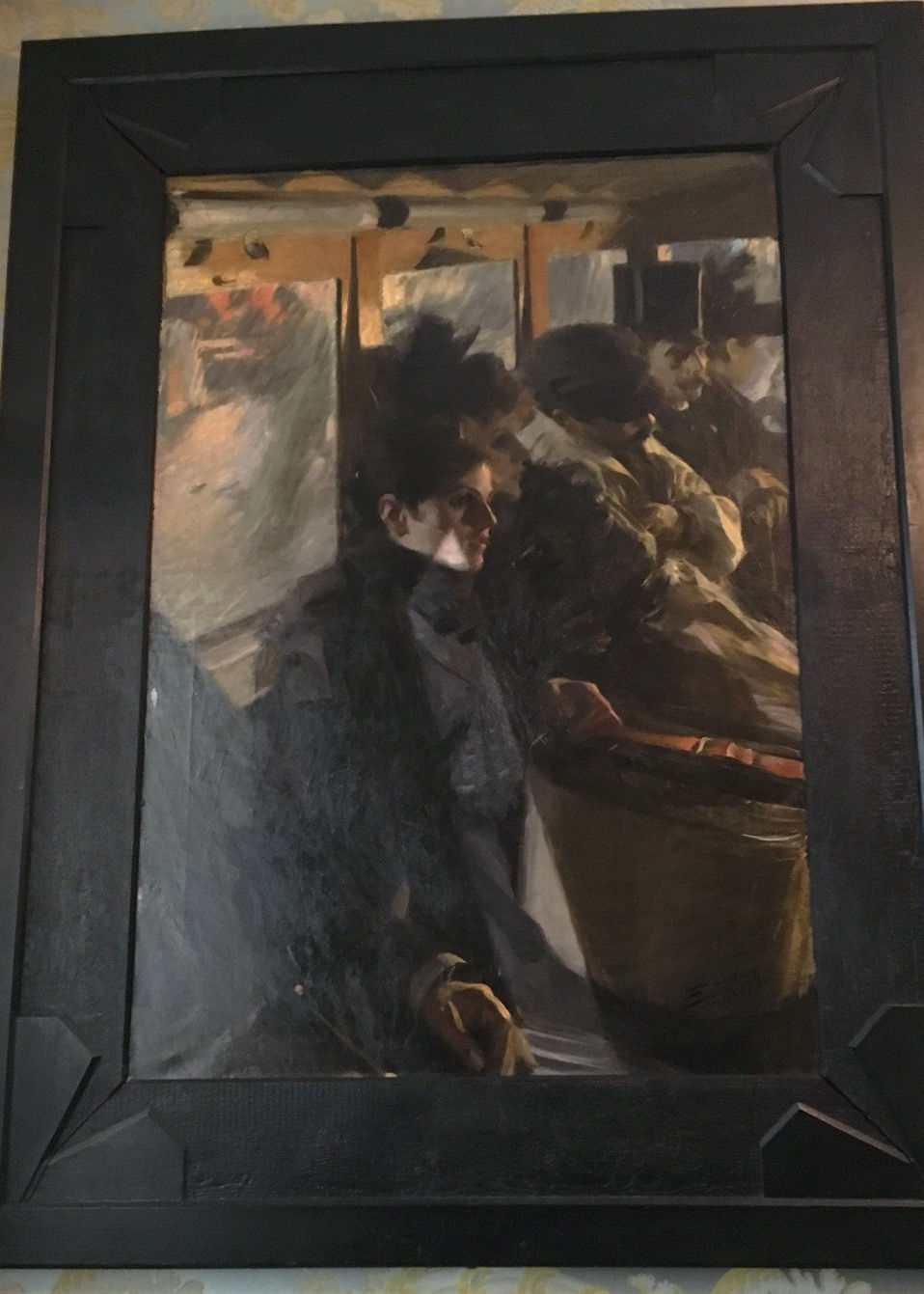

The Blue Room, another relatively small space, houses many of Gardner’s important nineteenth-century pieces, works by Manet, Sargent, Zorn, Delacroix, and Corot. Glass cases display letters and photographs of literary figures to whom Gardner was acquainted, such as Walt Whitman, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry James, and Waldo Emerson. Below, is The Omnibus by Anders Zorn (1860 - 1920), a prominent Swedish Impressionist.

Another Sargent painting, Mme Gautreau Drinking a Toast. Gautreau was the subject of Sargent's scandalous Madame X in 1884.

Finally, the MacKnight Room, used as private parlor and guest room, seems the most personal space in the rooms open to the public. On a bookshelf leans a 1922 watercolor of Gardner depicting her at age eight-two, after a debilitating stroke in 1919. The work, of course, is by her good friend, John Singer Sargent.

When Gardner died in 1924, she left an endowment that provides for Fenway Court and its collection. Her will made Fenway Court a museum for the ”education and enjoyment of the public forever.”

Should you travel to Boston, make sure you spend time at Fenway Court. If you still have room in your schedule, feel free to attend a game at Fenway Park. Isabella Stewart Gardner, it seems, “delighted in the Boston Red Sox.”

Comments